PERSONAL ESSAYS…

There is no revolution without joy

By Linda Mason Hunter

April, 2025

Lest we lose our sense of humor in these trying times, here’s a bit of sarcasm from that giant of topical humor The New Yorker magazine. This anecdote appeared in the Shouts & Murmurs column of the April 14, 2025 issue. Titled “Straw Man” by John Kenney, the article is a mocking riff on the recent United States policy to end the use of paper straws, as decreed by a memo from the Office of the Attorney General of the United States dated March 11, 2025. To wit: “Justice Department components shall take appropriate action to identify and eliminate any portion of policy or guidance documents designed to disfavor plastic straws.”

Here’s The New Yorker’s sardonic reply: “It is the policy of the United States to end the use of Dijon mustard. Mustard is yellow and made in America and not in France. France is a stupid place. The Justice Department and components will identify and eliminate any mustard that isn’t yellow French’s Mustard, although henceforth the name ‘French’s’ will be eliminated in favor of the word ‘Normal.’ This policy enforces not only the use of yellow mustard but also the use of such condiments as chutney and piccalilli. The words ‘chutney’ and ‘piccalilli’ are, as of this writing, illegal in the United States, because no one knows what they are.”

And that, my friends, is a snapshot of what our of United States government in Washington DC is up to these days. Beware. Take heart. And keep your sense of humor for there is no revolution without joy.

Source:https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2025/04/14/return-of-the-plastic-straw

Focus!

By Linda Mason Hunter

February, 2025

I just finished reading a relevant book I wish everyone would read. It’s called Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention, and How to Think Deeply Again, byJohann Hari. Its main premise is that our ability to pay attention is collapsing. In the United States, teenagers can focus on one task for only 65 seconds at a time, and office workers average only three minutes.

In doing research for this book, Hari discovered a basic scientific fact: The human brain can only focus on one thing at a time. It’s simply not humanly possible to focus on two things at once. So, when, for example, you are trying to write a coherent sentence (as I am now) and you get a ping on your phone, or when you start switching from device to device, from tab to tab, your attention diminishes, you get frustrated, the quality of your work suffers. When this occurs all day, day after day, it re-routes the synapses in your brain. Pretty soon, you find it impossible to think deeply at all. Your brain is frazzeled. You realize you don’t have some of the pleasure in life you used to have.

This is happening to us on a global scale. The world is speeding up, and that process is shrinking our collective attention span. Social media is a major accelerant. As our world experience gets faster and faster, we have been focusing on any one topic less and less.

Hari lays the root of the problem squarely on economic growth—the belief that the economy, and each individual company in it, should get bigger and bigger. That’s how we define success. Corporations need to find new markets by inventing something new. In this way corporations are constantly finding ways to cram more stuff into the same amount of time.

Hari believes we should abandon economic growth as the driving principle of the economy and instead choose a different set of goals. We could redefine prosperity to mean having time to spend with our children, or to be in nature, or to sleep, or to dream, or to have secure work. Most people don’t want a fast life—they want a good life.

It’s a crisis for the human species, but there are solutions. Hari explains what they are in this book. If we achieve these goals, the ability of people to pay attention would, over time, dramatically improve. Then we will have a solid core of focus that we could use to take the fight for a better world further and deeper.

It’s worth your time to read this book.

The inestimable value of friendship

By Linda Mason Hunter

June, 2025

I’m a big fan of Native American cultures, those who placed the highest value on the simple life, usually lived out of doors, with keen and enduring respect for nature. The things they hold sacred never fail to inspire me.

One of my favorite books is The Soul of the Indian, by Charles Alexander Eastman. In the chapter called “The Family Alter” he defines true friendship. In this passage he writes from the male point of view, but his words are just as true for women as they are for men.

“Friendship is held to be the severest test of character. It is easy, we think, to be loyal to family and clan, whose blood is in our own veins. Love between man and woman is founded on the mating instinct and is not free from desire and self-seeking. But to have a friend, and to be true under any and all trials, is the mark of a man!

“The highest type of friendship is the relation of ‘brother-friend’ or ‘life-and-death friend.’ This bond is between man and man, is usually formed in early youth, and can only be broken by death. It is the essence of comradeship and fraternal love, without thought of pleasure or gain, but rather for moral support and inspiration. Each is vowed to die for the other, if need be, and nothing is denied the brother-friend, but neither is anything required that is not in accord with the highest conceptions of the Indian mind.”

This type of friendship is something we can all aspire to.

My Father (1919-2021)

By Linda Mason Hunter

September, 2021

Ronald in 1942

I am 75 years old. My father died in May at 102 years old. It’s odd being on the planet without my father. He thought himself immortal for so long even his family believed it.

A few months before enlisting he met Alice Kenworthy, a striking dark-haired journalist, at the University of Iowa. They married in 1942 before Ronald shipped out for North Africa, flying combat missions up the Iberian Peninsula and south off the coast of Casablanca, up to the Bay of Biscayne, once returning to the airbase with 124 bullet holes in his twin-engine flying boat, a PBY Catalina. Flying below 2000 feet for up to 19 hours at a stretch he witnessed many fiery crashes, experienced several close calls, and lost many mates. In one squadron, only he and one other survived. With relief he came State-side after a year to an airbase on Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay where he tested planes, flying them until they broke down to see how long various parts would last.

After hostilities ended, the Navy assigned him to Puerto Rico and Newfoundland before he mustered out as lieutenant commander in 1948 and settled in Des Moines with his wife and two kids in a bungalow next door to Alice’s parents on Hickman Road. He graduated from Drake University Law School in 1951, then practiced law in the Farm Bureau firm of Stephens, Buckingham, Seitzinger and Mason for 28 years before retiring at age 60 and reinventing himself as a cattle rancher and land developer. He and Alice traveled the world, spending winters in Nayarit, Mexico. They subsequently retired to Edgewater Wesley Life in West Des Moines where he lived independently cooking his own meals in a bachelor apartment for the four years following Alice’s death.

His was a colorful life punctuated with risky adventures. He rode the rails as a hobo during the Great Depression; moved 28-ton granite boulders on the road in the dark of night to mark a grand prairie entrance to the housing development he created near Adel. He midwifed breached calves, feeding orphans with a baby bottle, and built two idiosyncratic houses with stone hauled from his quarry and lumber he milled himself using an old Chevy motor he rebuilt.

Cheerful and optimistic by nature, his self-focused personality was beset with contradictions. He could be a ruthless negotiator and a wounding scold. As a teenage running back on the Orient High School football team, he knitted himself a letter sweater from scratch, carding and spinning the wool from the fleece of a neighbor’s sheep. In old age he played the part of a beneficent Santa Claus, yet claimed to not like children.

He was “a tough old bird” with a contagious laugh, a family man in a cowboy hat, a long-winded story-teller, an embarrassing practical joker. One-of-a-kind. A character. A legend. We miss him.

A legend for those who knew him, at 102 ½ he was in excellent physical and mental condition. High school slender with a strong heart, healthy lungs, sharp mind, impeccable memory. His white beard and bushy eyebrows made him an authentic Papa Noel at Christmastime. To celebrate his 100th year he parachuted out of an airplane for the first time, a story that landed on Page One of The Des Moines Register. He exercised in the gym for an hour every day, and walked briskly and purposefully, standing straight and tall, eyes straight ahead, without the aid of a cane or walker.

Uncanny luck followed him like a muse throughout his extraordinary life. On the busiest Saturdays, for example, he could find a parking spot by the front door of Dahl’s supermarket in Beaverdale. Only a pair of thick work boots saved him from hacking off a few toes with a hatchet while teaching his children how to cut firewood.

Fate struck in early June in the form of a banal accident. Relaxing in his Lazy Boy, dressed for the gym in sweat pants, t-shirt, and terrycloth sweatband, his adjustable recliner catapulted him to his feet. The impact fractured his right femur at the hip, sending him powerless to the floor. Surgery proved painful. He wanted to die. So, he did. Like most everything he did in life, it was what he wanted so he willed it into being.

Ronald Eugene Mason, Sr. was born January 20, 1919 in Orient, Iowa during the 1918 flu pandemic which killed his older baby brother. His father Floyd Mason, Orient’s mayor, worked as a bank clerk and mechanic with his own shop. His mother Nelle operated a boarding house and helped manage Orient’s busy grain elevator, a regular stop on the Rock Island line.

Four dominant influences determined the course of Ron’s life. Growing up during the Great Depression created an exaggerated focus on money. As a boy, his father generated an early fascination with flying by taking him to a field near Greenfield to meet Charles Lindberg and touch his famous monoplane, the Spirit of St. Louis, during the aviator’s three-month tour of the U.S. As a youth, his grandfather taught him how to read Iowa land, buying low and selling high. During WW II, he enlisted for hazardous duty as a 23-year-old Navy Fly Boy, joining the only Naval squadron intercepting German ships and submarines going to and from the Mediterranean through the Straits of Gibraltar.

100 years old, sky diving for the first time.

The Day Earth Got a Fever

By Linda Mason Hunter

copyright Linda Mason Hunter, 2020

Alice Marie Kenworthy Mason

March 29, 2020

Strange times, indeed. Our days pass in the comfort of our home knowing we are loved and have lived full, meaningful lives. I always suspected there’d be a “war” of some kind in my lifetime, something challenging and life-changing that would affect the masses and make us afraid. It was inevitable, looking at history. This is that war, arriving with an odd name: “COVID-19.”

We are tested in times of war. I think of my mother at 23 years old sleeping in her childhood bed with a new baby by

her side, living with her parents, helping them in the victory garden, canning in the kitchen, rationing food stamps, waiting for news from the Pacific, where her brother was a Navy Seal swimming through the ocean with a knife in his teeth, clearing the beaches of Japan. Her new husband an aviator flying over the Atlantic bombing ships, scouting for submarines, dodging surface-to-air missiles. How difficult and heart-heavy it must have been to be safe at home, listening to the radio, anticipating mail delivery, dreading each knock at the door, and waiting, waiting, not knowing when or how it would end.

I'm confident they didn't complain. I'm confident they lifted each other up. I'm confident they got out of bed each morning resolved to channel their better angels. They all survived. Now it’s our turn.

Girlfriends

By Linda Mason Hunter

Me, Jane, Jayme (left to right)

Jayme and I were girlfriends. We did girlfriend things together. It started in the mid-1980s with “Friday Afternoons,” a casual salon centered around frank, honest communication—three knowledge-hungry psychologists and me, a stuttering journalist nursing a childhood wound. Before long these wise and witty women became my support group.

Though busy mothers in our 30s and 40s—juggling families and careers, tiptoeing through a minefield of challenges—we managed to show up at 4:00 once a month for the better part of 20 years. Boldly and tirelessly we navigated personal relationships, shared secrets, pondered life’s persistent questions, and laughed. We laughed at everything. We took strength from one another. We were girlfriends.

Our families (difficult constellations of yours, mine, and ours) challenged each of us in different ways. Sandra was the primary mother of five stepchildren, each a year or two apart. I was blending my two with my husband’s two under the same roof. But Jayme’s family took the prize for complication. Her two children from her first marriage shared half siblings from two other mothers and two separate fathers, then she had two more children from her second marriage. Whew!

Jayme loved her children with a ferocity that outmatched even my own. Her parenting advice remains the soundest I’ve ever heard: "The goal is to love your kids unconditionally, use M&Ms when needed, and get to the car without saying ‘Goddammit.'" Her grandchildren never failed to delight her. When my first grandchild was born Jayme sent me roses.

Jayme was my girlfriend. We sang and danced and giggled and skipped and did girlfriend things together. She always told us she’d die first. Godspeed, Jayme. Here’s to a peaceful crossing. I know you aren’t far away.

The Purpose of Life is Life

rina swentzell,tewa elder, discusses pueblo cosmology

By Linda Mason Hunter

copyright Linda Mason Hunter, 2001

Rina Swentzell, 2004

August, 2019

When I first interviewed Rina Swentzell, PhD (1939-2015), distinguished scholar and artist, she was living in an adobe solar house she designed and built outside Santa Fe, New Mexico. Reared primarily by her great grandmother in nearby Santa Clara Pueblo, she grew into awareness coiling pots and building houses, nourished by tales of her ancestors, indigenous Anasazi people thought to have traveled from Mesa Verde in the Four Corners region of southern Colorado 700 years ago to settle a series of villages dotting the banks of the Rio Grande in northern New Mexico.

Old traditions became faint memories during Rina’s lifetime. By the time I interviewed her in 2000, she was one of the few “traditional” Tewa women left who remembered the old ways. Even she was left with faint memories of “those gone before us.,” their way of knowing, thinking, and being on this land.

According to Pueblo cosmology people are not separate from nature. They are one with the natural universe, an insoluble connection that has existed from the beginning of time. Rina’s ancestors lived intimately with the life forces of the earth. They had a keen awareness of clouds, rain, mountains. That awareness made them sensitive to the spirit within clay, wood, and rocks, materials they modeled into ceremonial and functional items for everyday use. In contrast, modern European/Christian cultures live separated from nature, believing human life is superior over all of creation. Nature is to be subdued, not listened to. It stands to reason that these two cultures, with their differing views on nature, attribute different meanings to life.

In the old Tewa tradition sacredness is recognized in everyday life--every act a benediction, every step a prayer. Nowhere in Pueblo myths do humans experience a fall from God’s grace. The people and their world are sacred and indivisible. It is a world thoroughly impregnated with the energy, purpose, and sense of creative natural forces.

On December 15th, Rina invited me into her home to discuss Pueblo cosmology. It was Christmastime and her house smelled of baking. We spent the afternoon over tea at her kitchen table, the low winter sun warming my back through a large window providing a view of distant dramas as the sun edged its way across the mountain moving toward solstice. In conversation Rina chose her words carefully, often with long pauses for thinking, adhering to the Tewa code of honoring the silence, for “the more one says the less one sees.”

Q: Tell me about yourself, your background, what got you where you are today.

A: I was born in Santa Clara Pueblo in 1939, the third of eight children. English is my second language because the Pueblos at the time were much more intact than they are now, socially and economically. Growing up there is like a memory from another world. I went to the BIA (Bureau of Indian Affairs) Day Schools there. I loved going to school.

I actually didn’t grow up in my mother’s house. I grew up in my great grandmother’s house but was in and out of my mother’s house, as well. My primary connection was always with my great grandmother.

I left Santa Clara Pueblo after high school and went to college in Las Vegas, New Mexico, where I met my husband. Then I went to Texas, and came back again and did some teaching for a while in elementary and secondary schools. I had my children during that time—four of them, one boy and three girls.

As they were growing up I started making pottery. I grew up with people making pottery and building houses from mud. As a child I did all that. These are all my pieces (gestures to lovely mellow pots on shelves and countertops in her kitchen). They are all made of clay, but I wanted to be able to put them in the oven and eat off them. Pueblo pottery at the time had moved into decorative art and I wanted the functional back again. So I took the same clays and fired them at higher temperatures to make them usable in the kitchen. They look different, of course, but it was what I wanted to do. I threw them on the wheel (traditional Pueblo pottery is hand coiled). I did that for many years before I went to architecture school.

I got a Masters in Architecture at the University of New Mexico. My children were in school at the time so I drove to Albuquerque (65 miles away) every day for four years. I still don’t know how I did it. It was an incredible feat. I was incensed with the low income houses being put up by the government in the Pueblos. It was just tearing the fabric out of the community. I was really distraught that people weren’t building their own houses any more. Houses were being built for them, and they were paying ten dollars a month for a frame built by a subcontractor (“sub” in many ways). The locus of the main plaza was being destroyed by these individual houses, destroying the sense of communality.

I felt that whole world was being destroyed and being destroyed at a pace that I knew would destroy the whole community. And it has. No one has the same sense of community any more. And a lot of it was the individual houses, and the synthetic materials being used, and the sense of not owning your own house any more. That’s what drove me to study architecture. I couldn’t understand.

Growing up in that community, whenever anyone needed a house you went out there and started mixing mud. We built adobes. We did it. That was just the way it was. It was a great way to sustain community because as we were working on the house people would come by and help. When you do it, the energy’s there.

These new houses being built today are not places that have soul and breath, that you can relate to and interact with. More than anything growing up in that way of thinking, I couldn’t understand why, why the American world would build houses the way they built them. That’s why I went to architecture school, to find why do they do this, where are they coming from.

I found out it’s a very strange narrow world. My goal was not to have an architecture business, my goal was to try to understand what the world was about.

Q: Do you understand now?

A: To a certain extent I understand. It was really enlightening. Design, philosophy, story, all that was absolutely fascinating to me. Americans look at housing and shelter in a very different way than Pueblo people do. We look at it as energy. In American architecture there is very little emphasis on the spirit of place. It was assumed spirit was there. It’s a very masculine approach to building. Houses are seen as massive construction instead of as a place for someone to live.

When someone needed a house in the Pueblo, we would build a place for them. There was that sense of place. The act of building—materials, design—the whole thing is related. It’s all tied up with who you think you are.

And of course we grew up believing—the primary thing—in the breath of the world that we’re all a part of. That when I take a breath it’s the same breath as is in that cloud out there. We’re really cosmically connected. Everything is breathing. It’s not a notion of separation. I’m in one sense very much a part of this house because I am breathing it in. Po-wa-ha—wind, water, breath.

The house has breath. Its breath is affected by what is in the house and the people who come into it. When someone walks into a place their smell, their energy gets left there, and that affects the materials. So when anyone enters a house they really are affecting the energy of the house. It becomes a real interactive place.

Wherever you walk you affect the spirit of the place. We love to visit those old ruins because we believe that spirit is out there. We can walk in history with that energy. The ground itself remembers who walked there. We take deep breaths to breathe in energy. I can breathe in the breath of “those gone before us” in such places. Pueblo tradition tells us that we leave our sweat and breath wherever we go. The place never forgets us.

Even more, the structures we build also have breath. They are alive and participate in their own cycles of life and earth and of those who have lived within them. We believe the purpose of life is to be intimately united with nature. Everything is included in that connectedness. Houses, for instance, are “fed” cornmeal after construction, so that they may have a good life. Clay (dirt) is talked to because it is of the earth and shares in the flow of life.

To me this world view makes all the sense in the world. If you believe everything is cosmically connected you actually move through the world in a different way. If you believe a place is alive you step on it in different ways. You move around it in a different way. You move around everything in a different way.

Your coming into my house is a momentous occasion for me. Respect is expected. That’s the basic premise. You cannot move without affecting the cosmos where you are.

Q: So you believe houses have energy, much as people do?

A: Yes. People in the Pueblos believe that houses are alive. Different houses have different energies, or personalities. That was really how we operated. And all of that was destroyed by government housing—that whole idea that when you build a house you did it in a conscious, aware way. Those old houses were blessed before any of the walls went up. And through the whole process the people had communication with the walls. When the old houses were built the roofs were seen as the sky and the walls, made out of mud, were seen as the earth. Our whole cosmology was replicated in the house. It becomes than a miniature cosmos, a sacred place. You are reminded of it every day, that you live there in that world.

I think there are all sorts of energies that dwell in the walls and the floors of houses. And sometimes there are not good houses. You know when you go into a house that is not very good. We have ceremonies to rebalance the energy in houses like that.

Throughout its lifetime the house is continually blessed and healed. Women were generally in charge of this domestic duty. Houses get sick, like people, and need to be healed. When people die they get buried in the floor. So you live with all this energy that is constantly recreating the place. And the house went through different cycles with all of the things that were happening. That constantly had to be paid attention to.

Q: What can make bad energy in a house?

A: It may be mean thoughts, or violent things happen in the house. Unhappy things happen. Any of those things made a wound that becomes very intense and stays in the walls. All sorts of things.

Q: Do you consider the kind of industrial materials most Americans build with—drywall and pressed wood and fiberglass insulation, that sort of thing—to be dead materials?

A: I don’t believe anything is dead. It’s just a different kind of energy. I think everything in our world is alive. We may not like the kind of energy a certain material has, but it is alive. Drywall has a different personality, a different character. Some of it is natural material. Gypsum is natural. The process makes all the difference in the world. That’s why the way we move, the way we create, is important (sighs).

I think we’re talking about the difference between a feminine world and a masculine world. Men do things in a very different way than women do. I love to build with my daughters. I can work with them in a cooperative way. We all built this house together. We built the straw-bale house down below us. And the long, skinny shed. But we all feel that as soon as a man enters it becomes like you’ve got to get the measurements right, you’ve got to do this, and you can’t stop just when you feel like having some tea. When left on our own we flow. We stop when it’s time to eat some watermelon. We have a different rhythm so the end result is different.

I think the real challenge in life is how we bring that other into our world, how we get some sort of balance. The Pueblo world is always talking about opposite energies at work in the world. They see male and female as the primary extension of that at the cosmic level. They sky is male, the earth is female. How have they managed to create a hole at which we live? Energies need to be brought together in order for incredible creativity to take place. Without that male and that female life would not have happened. Or without male and female coming together life won’t happen. You can’t have creativity without tension. Tension is just inherent in the world.

Q: We aren’t looking for an absence of tension?

A: No. We accept tension. Tension is there. We just learn to live with it. We’re looking for how two opposites come together with tension but with harmony. That state can’t last for very long. Everything is in a state of flux. We know that nothing remains static forever. When opposites come together and there’s some tension, and they’re going to stay there for a while, it’s beautiful. It’s actually exquisite, that tension where creativity occurs. It’s a lifting of veils, a way of perceiving.

Nature teaches us. We take in everything that happens in nature. Of course in New Mexico we see it every single day. The clouds come over the mountains and they begin to form and billow, and snow comes down for a while, and then before you know it the sun is out and there are patches of beautiful blue sky. Before long everything is roiling and moving around again. With all that movement we get no rain. We’re so intensely aware of it here in the desert. We’re just on the brink of being able to survive.

Imagine in earlier days we didn’t have gas stations, we didn’t have grocery stores, none of that kind of stuff that separates us from really feeling the place we live in. The Pueblo philosophy comes from really feeling the place we live

in. It comes from just living on the edge of being able to survive. When those clouds are coming there’s promise of rain, that’s about as exciting as it gets. To get a few drops of rain on this place, of some snow, and to be right there with it, that’s a moment of creation.

It is a very female-oriented way of looking at the world. We didn’t develop a notion of God or heaven. The idea is that we live here. The interaction between sky and earth gave birth to all living beings. We literally see ourselves as part of that coming together. So, we relate to the earth and behave towards it in a very different way than you do if you believe this is all and there is no more. The sky and the earth gave birth to this plane.

Our cosmology is close to the Gaia concept. The human person who gives you birth is also a gia (pronounced gee-a). Women in that traditional community who take care of the entire extended family are also known as gias.

The interesting thing is the whole social and political organization is between winter and summer people. Those opposites again, coming together in order to create the whole community. Usually a male leader serves as a guide for the winter people and another as a guide for the summer people. When one of those leaders finally achieves a certain status they also become gia, they become other. Gia translates literally as mother. They become mother in that larger community. It’s reinforced at different levels that the ideal person is a mother, or Gia.

European Western thinking is very different with God up above and a heaven there and everything moving upward towards a male figure. Western thought is oriented towards maleness. Although in Christ you begin to have the softer side, more love. But it’s primarily God, finally. A very, very different focus.

When you focus on the earth as the mother you came from, and you know it in a very deep way, of course you treat the earth in a different way, and you aren’t thinking of leaving a dirty place. The world for us as people is “Nung.” And the word for earth, the stuff the earth is made of, is “nung.” Identification is there. We are earth.

Q: What happens to the soul when the physical body dies?

A: Our breath leaves. Our breath doesn’t flow through us any more, it returns back to the movement of the sky, and that movement that keeps everything alive while our bodies melt back into the earth. The spirit becomes part of the breeze, the wind, the clouds. It integrates back into the exquisite being that we’re part of. Existence is not determined by a physical body but by the breath, symbolized by the movement of wind and water.

That cosmology gives you a very different sense of place. Everything is sacred. It isn’t like in Western thinking where there is the notion that the earth is a dirty place you want to get away from. You can’t create love in a deep way if you think that real joy and glory is yet to come.

Q: Is the spirit at home when it leaves the body?

A: This is it. The whole thing is always home. You don’t go anywhere. It’s not really a transition when your spirit leaves the body. Death isn’t meant to be frightening. It doesn’t change all that much. Sure, we are transformed in some ways, but we’re still part of the working of the whole thing. It’s not individual soul that remains.

It’s not a separation but a coming together. That’s the whole cycle of life. We don’t pull out and separate from this thing. We remain a part of its fate.

Q: What does one strive for on earth?

A: One strives to be a mother, and that is a loving, giving, nurturing, harmonious person. And the gesture is that (opening her arms). It’s encompassing. It’s a hug. It’s love. In our community, the old community, all the stories and songs are always about asking for love from the cosmos. Asking to be loved and to love. It’s what we all want. That’s the heart of it.

This place, this time, is all that there is. There is no heaven, no God. This place is where it all happens—happiness, sadness, pain, obligations, responsibility, joy. Human life, in the traditional Pueblo world, is based on philosophical premises that promote consideration, compassion, and gentleness towards both human and non-human beings. In this thinking, every act or thought has an effect on the configuration and feeling of the whole of existence. Rituals, dances, and songs, even today, are about achieving harmony with the life force, the po-wa-ha.

Q: Where does art fit in?

A: We don’t have a word for art. It’s that act of doing what you have to do every moment in the best way you can. That’s what art is. Anything is art as long as you are doing absolutely the best you possibly can. The focus is on the doing rather than the product. It has to be done with that sense of, “I am capable of loving. I am capable of taking love. This is what I have to do before me right now. I will hold it as lovingly as I can. I become an act of art.”

The Orientals are so great at it—putting out some tea and making it beautiful, it becomes art. I think you do it as ritual. That’s why the dance is so important.

One thing we’ve always heard is to walk carefully. That’s another art form. Walk carefully so you’re aware of everything around you.

Q: Pueblo people are known for their powerful dances and feast days. What are your dances for?

A: Dances are symbolic rituals, extremely symbolic. They occur outdoors. Your feet are touching the ground. You are wearing the tablitas on your head, a turquoise headdress with symbols of clouds and mountains on it. So you are bringing those two energies through you, thus becoming a part of that sacredness. It’s very symbolic.

Pueblo dances help center the people in this mindset. Dances are for communication with the clouds and the wind, for getting in touch with other realms of existence. The dances literally bring that cosmic breath to the landscape and to the human community. And knowing that not welcoming that breath of the larger world into the human place would be unhealthy. Humans cannot be isolated within their own world.

Dancing is a spiritual exercise lifting the veil between realities, between this world and the next. In the dance we live for a time in a venerable holding pattern, in the dancing circle, what we call the middle heart place between earth and sky, hovering in a super-reality that is at once the sub-conscious and conscious self. In this hallucinatory place you dance to honor the meaning of life. All life. To honor the earth as our home, the supporter of all life. It’s a delicate dance.

The kitchen corner of Rina’s adobe house where we talked.

Q: Tell me about your house.

A: The whole house is solar. The entire south side is glass. A wood stove provides supplemental heat. My husband has an electric heater in his room. He likes a much more constant comfort. But the way I grew up in the Pueblo you went with the ups and downs. You were expected to. It’s winter time of course you’re supposed to be cold. You can’t have the constant temperature that’s the expectation today. That constancy takes the personality out of the house.

This house is very different from any other house I’ve ever lived in. and it’s the most responsive to what’s happening outside. It’s a wonderfully sensitive house in that as soon as the sun comes up in the morning the living area (the lowest part of the house) is just flooded with sun. You feel the heat coming from the sun and it’s wonderful. You’re wide awake then because you’re supposed to be—the sun is up. The bedrooms in the back remain dark and cool for a while. By the time the sun goes down the back rooms are warmed up and you’re ready to go to bed. The living area cools down through the night, but no one is using this area during the night. So the temperature moves around in this way, changing with the day, with the season. With all the windows I can watch the seasons change. Through the clerestories I can watch the sun as it travels across the sky.

Even if the outside temperature goes down to zero the house remains very livable. I haven’t used the fireplace now for going on the third day because the house is so warm. Then you have to be aware of the clouds, like I did before you came over. I was thinking, “Oh boy, we’re go have to build a fire.” The house allows me to take part in the changes going on outside. It’s a conscious thing.

Q: How were the old Pueblos structured?

A: Pueblo people are very ego-centric. They live at the center of the universe. The heart of the earth is “bu-ping-geh” (heart of the Pueblo), which for the Tewa people is the open community space within the village where ritual dances take place. The bu-ping-geh contains the literal center of the earth or the “nan-sipu,” which translates as the belly-root of the earth. Each Pueblo cosmos encircles the nan-sipu, and the surrounding areas where the sky and earth touch are the boundaries of the well-organized spaces for people, animals, and spirits to live.

All built structures were not meant to last forever but rather to meet immediate needs. And they were built to be beautiful, within human scale, using accessible, simple materials—mud, wood, and stone. They were constantly modified to fit their use. Beliefs and values were clearly expressed in those structures. Houses were not material symbols of wealth but were, rather, an elegantly simple expression of human shelter.

In the Pueblo there were no manipulated outdoor areas that serve to distinguish humans from nature. There were no areas where nature was domesticated. Within the Pueblo outdoor and indoor spaces flowed freely and were hardly distinguishable. One moved in bare feet from interior dirt floors enclosed by mud walls to the well-packed dirt smoothness of the Pueblo plaza. All senses were utilized in this movement. Each of the various dirt surfaces (interior walls, outdoor walls, plaza floor) were touched, smelled, and tasted. We carried special rocks in our mouths so that their energy would flow into us. Everything was touchable, knowable, accessible.

Q: How would you fix housing on the Pueblo today?

A: I would get the people to build their houses themselves. That was my whole frustration at the time I went to architecture school. Why don’t they just set it up so these people remember how to build their own houses? I don’t know why they can’t. They used to just a few years ago. They all knew how to. Five years later, 30 years later, no one can remember how to do it.

People don’t see that it’s a process, that the way you do it is very meaningful—the kind of materials that you use, and the way in which things get put together. Hammering nails is a masculine thing. It takes strength, and it’s violent. If it were totally up to women it would not have evolved in that way. We have a different way of putting things together.

The way things are put together is very important—the materials that are used that allow women and children to be a part of it. Women don’t have the strength to build the standard American way. One of the things I find wrong with straw-bale building is the size of the bales. Women and children cannot work with them very well. They can’t lift them and set them down. You can lift up adobe block and set it down. Women can do that. That’s why a long time ago women would sit in a place and make round balls of adobe block. Kids carry them and help put them up. They’d do a little bit at a time. It was an understandable process, done as a family.

Q: Given that this earthly plane is often painful and confusing, and that people fight with each other and ruin their environment in so many ways, do you see the future as hopeful, or not?

A: What remains as hope in the end is that we all—Indian, non-Indian, artists, non-artists, rural or urban—desire that genuine experience of oneness with the breath of life that forms the world we live in. And I do believe that however we express ourselves we all yearn to feel the breath of the universe assuring us of our connection with the clouds, wind, rain, mountains—and with ourselves and each other.

It’s spiritual fulfillment rather than material acquisition. A way that affirms that all life expressions are of one spirit or breath. Our continued existence as one species of organism depends upon the breath, or spirit, that informs the whole universe.

1947

“It was midday. I sat next to my great-grandmother, Gia Khuun, against the south adobe wall of our Santa Clara Pueblo house. We wait quietly, listening to the buzzing of flies, when she caught the sound of an airplane in the distant sky. Gia Khuun was rubbing the loose, leathery skin of her hands when she reached for my hand to be quiet. The sound grew louder, we caught sight of the vapor trail and watched it disappear over Thunjo, Black Mesa. When the sound died, the buzzing of the flies resumed.

“This was 45 years ago and I was eight years old, yet I still remember the expression on Gia Khuun’s face and, mostly, the look in her eyes. She didn’t understand. We had never seen an airplane. We saw only vapor trails and heard the rumbling in the sky. What was happening?

Cars were a very recent part of our lives. When Gia Khuun first saw the car my father brought home, she walked around it with her palms out as if to caress, but could never quite touch it. I, on the other hand, nearly leapt into the backseat. As we drove over the dirt road toward the Pueblo day school and back again, she held onto the door handle and tightly squeezed my leg, holding on. That time, also, I felt her confusion, jolts of change were rattling her understanding of the world. It was 1947.”

--Written by Rina Swentzell, published in El Palacio (1992)

Aldo Leopold’s Sauk County Metamorphosis

By Linda Mason Hunter

September, 2019

What would the world be, once bereft

Of wet and of wildness? Let them be left,

O let them be left, wildness and wet;

Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet.

—Gerard Manley Hopkins

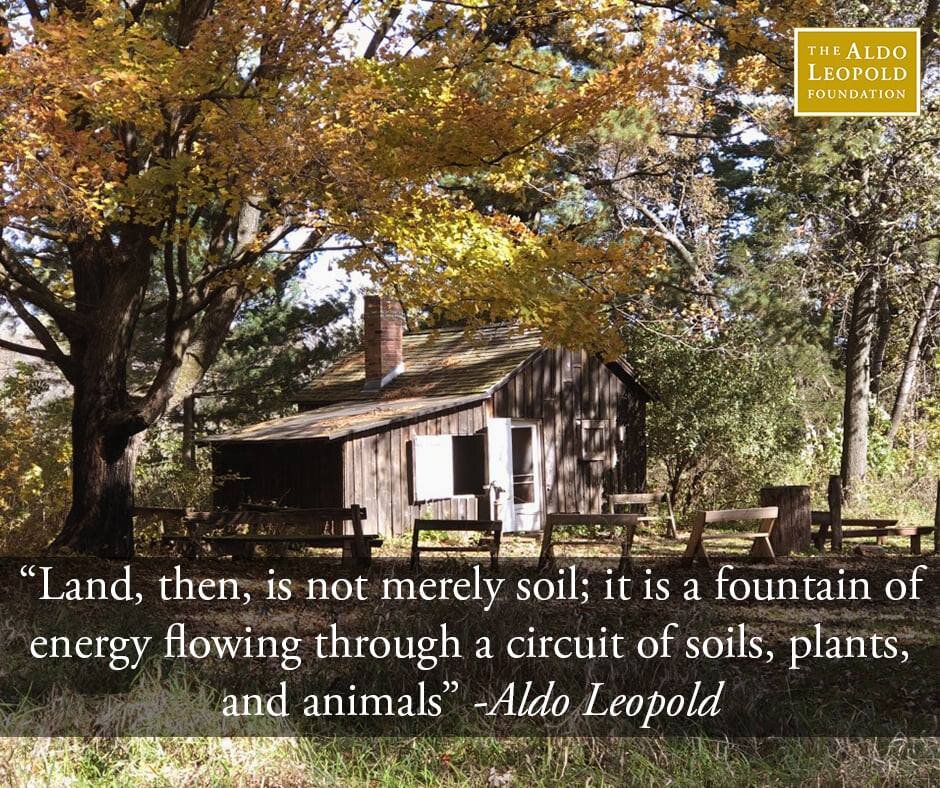

Last week, while road tripping through Wisconsin, I stumbled upon County T outside Baraboo. A small hand-painted sign with an arrow pointing down a quiet road, beckoned, “Aldo Leopold Shack and Land, 9 miles.” We drove over green rollercoaster hills, then turned off on a gravel road leading, after a fashion, to the door of Leopold’s famous “shack,” once a ramshackle chicken coop waist-deep in scat he and his family converted into a weekend retreat in the 1930s.

Like Thoreau at Walden, Leopold (known by some as the father of wildlife conservation) strived for the simple life, stripping away the comforts of modernity that he believed led to stress and an alienation from nature. Over the course of a few years, he and his family took 264 acres of used-up Dustbowl land bordering the Wisconsin River and turned it into the wild natural paradise it is today.

Leopold’s book, A Sand County Almanac (published in 1949), is a collection of personal essays advocating his “land ethic,” a responsible relationship existing between people and the land they inhabit. It’s a delightful read revealing how he became one with the land in order to save it.

“The Shack.” Photo courtesy of the Aldo Leopold Foundation

The property is now a historic site with a large lodge housing the Aldo Leopold Foundation. We toured the museum, learning more, then hiked the trail to see for ourselves how this scrub land was transformed into a fertile, wild environment of trees, prairie, flowers, and ponds, a place for both people and critters to live in harmony side by side..

If you get the chance, this is a worthwhile stop. Here’s a video of Leopold’s land today.

How to Handle Destructive Emotion

By Linda Mason Hunter

April, 2019

The March 18, 2019 issue of Time magazine documents the life of the 14th Dalai Lama, the foremost spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism, a wise and peaceful man considered a living Buddha of compassion. I’ve followed his teachings for some time now and find them an antidote to the hectic way of American life.

The 14th Dalai Lama

As I grow older I see the quiet, frugal life I knew as a child change at an alarming pace, and I worry for our children. Where is the time for reflection? Where is the time to be a good steward, a good neighbor, a good parent? The Dalai Lama, now 84 and slowing down, is worried, too. Here’s what he has to say about that.

“Western civilization is very much oriented toward materialistic life. But that culture generates too much stress, anxiety, and jealousy, all these things. So, my Number One commitment is to try to promote awareness of our inner values.”

The Dalai Lama believes that from kindergarten onward, children should be taught about taking care of emotion. “Whether religious or not, as a human being we should learn more about our system of emotion so that we can tackle destructive emotion in order to become more calm, have more inner peace.”

How do we tackle destructive emotion? First by recognizing it when we see it in ourselves. When you feel it rise up, take a deep breath—or two or three—calm down, and begin anew. It’s a challenge, but with practice it gets easier. Meditation helps, too, or some kind of mindfulness practice.

Learn not to engage in controlling, manipulative behaviors—like jealousy, guilt-tripping, threats, intimidation, gaslighting, violence--as are bound to occur in relationships. The way I deal with it isn’t perhaps the best way, but it works for me. I don't get mad; I get distant. When tension gets so hot I can't focus, I flee. I leave the room or hit the highway, going going going going until I reach a place where I can breathe again.

Deep breathing is strong medicine. Teach your children.

Source: Time magazine

Life is Good

By Linda Mason Hunter

April 12, 2018

What a way to end Mercury retrograde! Rode as copilot on a floatplane, with 180 degree views, from Gabriola Island to the port of Vancouver, British Columbia. "I'm a bit claustrophobic" I told the young pilot as I gingerly stepped through the door of the tiny plane. "Well then, why don't you sit up front with me," he replied.

Flying from Gabriola Island to the city of Vancouver

After strapping me in, he gave me a set of headphones to wear so I could hear him speak to me, as well as eavesdrop on the chatter of air traffic control. Then off we went, up up and away, over the Johnstone Strait with its numerous islands ringed with granite cliffs covered in pine, arbutus, cedar, and

spruce; me searching the sparkling ocean for signs of orca and dolphin, following the trail of tankers from all over the world headed for English Bay. Then, slipping through the mouth of the Bay, over the water past UBC and a string of beaches (there's mine! Kits Beach, where I live just up the hill). Around the tip of Stanley Park the plane descends to just a few feet off the water. I watch the Vancouver skyline creep closer and closer and lower and lower, until....we round a corner and splash! We are on the water, floating into the dock in the heart of downtown, just like a boat.

The smell of fossil fuel makes me lightheaded up here in the front of the plane. I spot a boat with a sign that reads "Spill cleanup." A shame it has to exist, but that doesn't dampen my spirits. The rain is over; spring has arrived with promised warmth, cheerful birdsong, and good karma. Wow!

Landing downtown Vancouver

Enchanted Light

By Linda Mason Hunter

October, 2018

I’d heard, of course, of the enchanted light in New Mexico, particularly the mountainous areas around Taos and Santa Fe which for centuries has attracted artists from all over the world. But it wasn’t until I experienced it that my soul understood.

Near Taos, October 2017. Photo by Linda Mason Hunter

It first happened on my initial drive into Santa Fe on I-25, with Albuquerque in my rear view mirror. It was springtime and the ochre desert, with its prickly cacti, was abloom with wildflowers, random bursts of crimson, hot pink, fuchsia, shades of blue, and gold. The sharp resinous taste of a single juniper berry, the residue of a recent hike in the desert,

Getting By, Getting Along

By Linda Mason Hunter

January, 2025

Today, with our country—and indeed the world--on the precipice of radical change, and so many suffering from life changes they didn’t anticipate, it’s often difficult to find happiness, not to mention contentment. Everywhere I go, everyone I talk to is asking the same question: what can I do to make the world a better place?

When life as we knew it yesterday is not the same today, it’s not an easy question to answer. But one thing each one of us can do to make our little corner of the world a better place is to engage in the simple practice of treating others as you want to be treated. What is known as the Golden Rule, an age-old tenet that is the first principle of every religion.

· In the Christian faith it’s “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”

· In Islam, it’s "None of you believes until he wishes for his brother what he wishes for himself.”

· Jewish and Buddhist interpretations are similar: "What is hateful unto you do not unto others."

It’s a simple common morality. But if religious teachings are not your thing, perhaps this quote from Kurt Vonnegut, one of my favorite authors, will be more to your liking:

“Hello, babies. Welcome to Earth. It's hot in the summer and cold in the winter. It's round and wet and crowded. At the outside, babies, you've got about a hundred years here. There's only one rule that I know of, babies—God damn it, you've got to be kind.”

lingered on my tongue. As I neared Santa Fe, the pungent smell of piñon logs burning in outdoor kivas drifted through the open windows of my car, tickling the hair in my nose.

With the sun slowly fading into the west behind me I caught a shimmer out the corner of my eye. Traffic was relatively heavy so I couldn’t fix my gaze on the shimmer. I could only glimpse it in small gulps. What caught my eye was a pale blue pickup truck rumbling peacefully along in the lane beside me. An ordinary beatup pickup right out of the early 1950s, with its rounded corners and bed packed with tools and lumber, the working vehicle of a carpenter or tradesman. The low sun was shining on it in a way that highlighted its contours, making the outline gleam and sparkle like it was the star of the road, an unearthly glow emanating from within its rusty metal. Something extraordinary. Magical. Once I knew what it was I couldn’t keep my eyes off it.

Enchanted light. It has to do with the altitude and the arid climate. 7500 feet, where oxygen is thin and the air dry, making the air clean, pure.

And the sky. Lapis blue surrounding you, punctuated with white fluffy clouds carrying the spirits of native ancestors who walked and built and loved and fought on this red earth. A cosmos hinting at mysteries within mysteries. A sky that pleads “Use all your stars” to those who walk below. As Willa Cather wrote in Death Comes for the Archbishop, “Elsewhere the sky is the roof of the world; but here the earth was the floor of the sky…the thing all about one, the world one actually lived in, was the sky, the sky!”